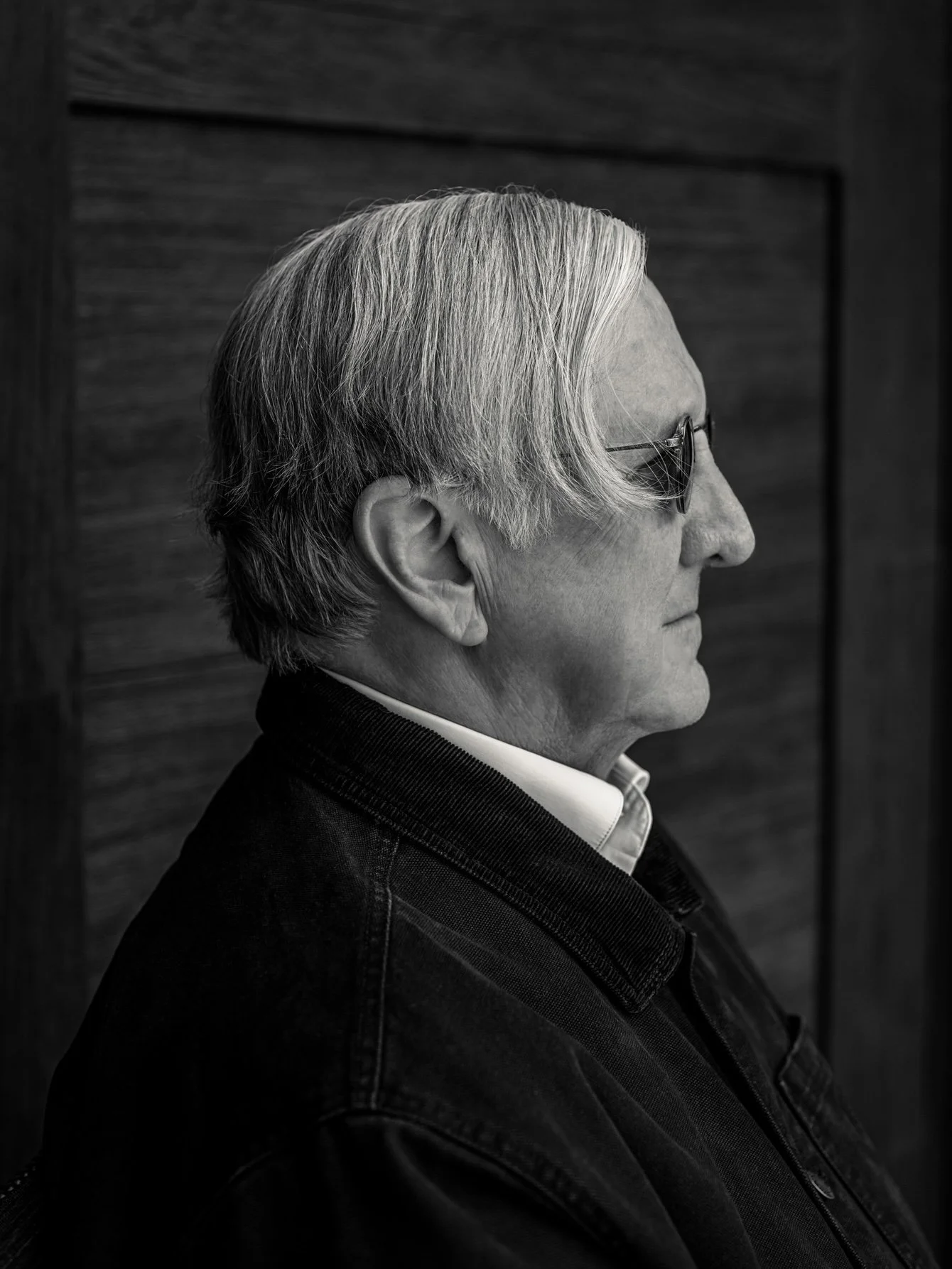

T-Bone Burnett unfolds his towering frame from a small chair in a live room inside Studio Z, his own corner of the historic Village studio complex in Los Angeles, and reassumes his post at the mixing board next door.

We’d already cased out most of the building, dodging scores of musicians milling on-break—all eight studios were booked on this early February afternoon—in search of a quiet spot to talk movies and a life in music. A booth filled with mic stands but no microphones suited us fine. Legs crossed, his white wingtips surrounded by Gretsch guitar cases covered in gaffers tape marked “T BONE”—a nickname that stuck since childhood—the 75-year-old Grammy- and Oscar-winning producer didn’t remain seated for long.

In the control room next door, while waiting for playback on his latest recording, a breeze blew open a window, scattering papers and production notes across the room, just as a Corgi of unknown origin wandered in from another studio.

The dog was circled by curious engineers, who welcomed him to the session. Soon, music filled the room. Throughout the two-minute track, T Bone was effusive in his praise for the singer, the West Virginia-born Sierra Ferrell. But the first snare hit didn’t sound right. Swap the second hit for the first one, T Bone suggests. His longtime engineer, Mike Piersante, nods. He’d added reverb to that first snare, tried everything. “Just replace it, that’s easier,” T Bone says casually with one foot out the door, signaling it was time once again to swap rooms.

The song sounded like it had always been there, like it could slot into any era. The combination of raw talent in a relaxed environment, captured with technical precision, is a hallmark of T Bone’s body of work. Settling back into his seat, he marveled at the opportunities for young musicians today and their accessibility to recordings that predate them by a century. “When we were starting out, you couldn’t find a Skip James record,” he says of the fingerpicking master of Delta blues, born in 1902.

“A lot of that music from the 1930s—the era of 78s—was wiped out in the second world war, because all the shellac was melted down to make paint for tanks and battleships. A whole library of music was shredded. There were only copies left around in people’s houses, that’s it. People have spent 90 years trying to resurrect that library as best they can. And now it’s all online. That’s good. The part that’s not good is that the most profound experience of music is to be in the room with the musician when he’s making it. And every step you get away from that, the less profound, the less intimate the experience gets.”

T Bone’s institutional memory of American music and his own contributions— beginning with his Texas rock group The Loose Ends in the mid-60s, later a tenure in Bob Dylan’s Rolling Thunder Revue, and decades of production for bold-faced names like The Who, Robert Plant, Willie Dixon, and Elton John—has made him an invaluable resource for filmmakers, as well.

T Bone’s been recruited to lend his authenticity to the creative industry in many different capacities. He has coached actors in their depiction of established musicians, as seen in Reese Witherspoon’s June Carter and Joaquin Phoenix’s Johnny Cash in Walk the Line (2005), curated standards and lost hymnals that evoke a far-gone past in the Cold Mountain (2003) and O Brother, Where Art Thou? (2000) soundtracks , disoriented viewers with the atmospheric score of HBO’s True Detective (2014-), and created a fictional character’s entire catalog from scratch, as he did with Jeff Bridges in his Oscar-winning portrayal as Bad Blake in Crazy Heart (2009) or Oscar Isaac’s folk turn in Inside Llewyn Davis (2013).

“Music onscreen was always disturbing to me,” T Bone says. “Even in the stuff we’ve done, I’m still disturbed by it. We never get it really right. The only time we got it really right was Inside Llewyn Davis, and that’s because Oscar Isaac is such a prodigious talent, such an amazing guitarist and singer. We drilled that music so hard. We shot every one of his songs handheld, almost documentary-style. I was sitting this far away from him,” he says, shrinking his hands from a foot apart to a clasp. “I had a stopwatch, timing measures. And he never sped up or slowed down once, so we could cut between any two takes.”